Hand-crafted precision:

Chow Keung, who learned to paint larger-than-life film posters as a teen, repainted six posters for the exhibition.

Hand-crafted precision:

Chow Keung, who learned to paint larger-than-life film posters as a teen, repainted six posters for the exhibition.

Oversized ad:

Chow Keung’s masterpiece poster for the film

The Boxer from Shantung (1972), is one of six on display.

Oversized ad:

Chow Keung’s masterpiece poster for the film

The Boxer from Shantung (1972), is one of six on display.

Lobby look-alike:

The exhibition hall was kitted out to make visitors feel as though they were transported into one of Hong Kong’s grand old cinemas.

Lobby look-alike:

The exhibition hall was kitted out to make visitors feel as though they were transported into one of Hong Kong’s grand old cinemas.

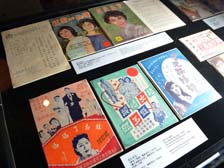

Box-office best-sellers:

Sought-after movie booklets, with photos and information on the film being screened, cost 20 cents in the 1950s and ‘60s, with revenue distributed to the staff as “tips”.

Box-office best-sellers:

Sought-after movie booklets, with photos and information on the film being screened, cost 20 cents in the 1950s and ‘60s, with revenue distributed to the staff as “tips”.

Class act:

Film tickets were categorised and charged according to seat locations – Front, Middle and Back Stalls.

Class act:

Film tickets were categorised and charged according to seat locations – Front, Middle and Back Stalls.

Crowd control:

The hand-drawn back-stall seating plan showed capacity reached about 800.

Crowd control:

The hand-drawn back-stall seating plan showed capacity reached about 800.

Silver screen gem:

The Royal Cinema, pictured in 1968, was located on Nathan Road in Prince Edward, near the location of today’s Pioneer Centre. (Photo provided by Hong Kong Film Archive)

Silver screen gem:

The Royal Cinema, pictured in 1968, was located on Nathan Road in Prince Edward, near the location of today’s Pioneer Centre. (Photo provided by Hong Kong Film Archive)

Memory lane:

Film Archive Programmer Cecilia Wong hopes the exhibit will stir up seniors’ recollections and help younger people appreciate the cinematic experience.

Memory lane:

Film Archive Programmer Cecilia Wong hopes the exhibit will stir up seniors’ recollections and help younger people appreciate the cinematic experience.

Posters recall silver screen’s golden era

February 09, 2014

Six larger-than-life posters on show at the Film Archive that veteran artisan Chow Keung carefully crafted recall the silver screen’s golden years in Hong Kong.

Chow, now aged 67, was born in Vietnam, where he tagged along with his mother to movie theatres when he was young. Her friend introduced him to the role of a theatre advertisement painter, and he was hooked.

At the age of 13, Chow became an apprentice in the trade in Ho Chi Minh City, where he learned the basics and became an independent poster artist after three years’ training. Soon after, he and his mother moved to Hong Kong.

Detail oriented

Though the posters to be hung on the façade outside a theatre were as large as 50 square metres, displayed at great distances from the crowds they were meant to attract, artists like Chow paid painstaking attention to detail.

To capture a movie star’s facial expression accurately, grids were laid over an original still from the film. Each grid cell was then painted onto the billboard on a greatly enlarged scale.

Words to appear on the poster were aligned using pre-drawn lines for accuracy.

Rainy days rued

Chow loathed having to produce posters in the rainy season.

“If it rained hard onto the poster, all the faces would start to blur as the colours were washed away. The most difficult part of my work was squatting down and using a spray bottle filled with a transparent glue to safeguard the poster, and prevent any run-off,” he said.

Afterwards, he often felt faint from the fumes, he added, noting it was the “hardest part” of the process.

Eclectic abilities

Painting posters was his calling, but there were only so many projects to keep him busy. In the late 1960s, Chow also opened a martial arts school in Hong Kong, and took up work as a movie stuntman.

In the early 1980s, as the number of cinemas in Hong Kong multiplied, Chow spent more of his time as a poster artist, working for Full House, Oscar, Ace and Good View theatres, among others.

By the end of the decade, demand for his hand-crafted posters declined as new technologies for mass producing them took off. Chow retired as a poster artist.

“Hand-painting posters is different. The new generation doesn’t understand the whole technique, the need for colour matching and design. It’s a pity,” he said.

Curtain rises again

Decades after his formal retirement, the Film Archive invited Chow to re-paint giant posters for six popular classic films: Wong Fei-hung, King of Lion Dance (1957), The Legend of Purple Hairpin (1959), The Merdeka Bridge (1959), Love Without End (1961), Sun, Moon & Star (1961) and The Boxer from Shantung (1972).

There is no longer a demand for such hand-drawn movie posters, but Chow hopes their display will help younger people appreciate the skill and care behind them.

Film Archive Programmer Cecilia Wong noted some of the reasons Chow’s first trade was eliminated. Large theatres were transformed into much smaller ones, and relocated inside shopping malls during the 1980s. That left no space available for hanging giant posters.

“Another reason was the cost. To create a poster required a master working with two to three apprentices. Their combined salaries were a high cost. Also, computerised painting techniques were advancing, as budgets shrunk.”

Chow’s oversize film posters are displayed along with about 130 archival treasures such as handbills, booklets, hand-drawn seating charts, tickets, weight scales, and photographs of Hong Kong’s old and beloved theatres.

Cinema trivia

Back in the day, movie-goers received a free handbill with a synopsis of the movie on it. There were also booklets available with more photos and film information. They usually cost about 20 cents - a substantial sum in the 1950s and '60s.

“The booklet revenue was usually distributed to the staff as ‘tips’. Box-office staff would slip the booklet in with the tickets, charging the extra without saying a word,” Ms Wong said.

“Now, movie-goers can buy tickets online, and contact between them and cinema staff is reduced. In the past, when a thousand people watched a film together in a theatre, the atmosphere was totally different. In the 1950s and '60s, it was common to see kids tagging along with adults to watch films. Parents would often buy just two tickets, and bring their children along for a night of entertainment,” she added.

She hopes the exhibition will stir up nostalgia for the good old days of cinema.

For exhibition details, visit the Film Archive website.