Moving music:

The qin’s quiet, low-pitched sounds caught Choi Chang-sau’s ear when he was young, prompting his lifelong commitment to making the instrument, and teaching others how to.

Moving music:

The qin’s quiet, low-pitched sounds caught Choi Chang-sau’s ear when he was young, prompting his lifelong commitment to making the instrument, and teaching others how to.

Enthusiastic instructor:

Over two decades, Mr Choi has introduced qin-making skills to more than 30 students.

Enthusiastic instructor:

Over two decades, Mr Choi has introduced qin-making skills to more than 30 students.

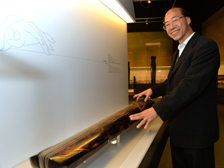

Qin master:

Mr Choi founded the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society to nurture qin makers and promote the qin-making art.

Qin master:

Mr Choi founded the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society to nurture qin makers and promote the qin-making art.

Dream weaver:

When his instructor failed to complete a full set of 12 qins, one for each of 12 poems he had penned in a series, Mr Choi did so, and invited celebrated Chinese scholar Prof Jao Tsung-I to write the calligraphy for them.

Dream weaver:

When his instructor failed to complete a full set of 12 qins, one for each of 12 poems he had penned in a series, Mr Choi did so, and invited celebrated Chinese scholar Prof Jao Tsung-I to write the calligraphy for them.

Scholarly pursuit:

Hong Kong Heritage Museum Curator Chow Hing-wah hopes exhibition visitors will gain an understanding of the relationships between the qin masters, the teachers and their students.

Scholarly pursuit:

Hong Kong Heritage Museum Curator Chow Hing-wah hopes exhibition visitors will gain an understanding of the relationships between the qin masters, the teachers and their students.

Redolent instrument:

This Ming Dynasty qin is said to emit a mild fragrance when played, which encourages qin students to learn to play it well.

Redolent instrument:

This Ming Dynasty qin is said to emit a mild fragrance when played, which encourages qin students to learn to play it well.

Intricate craft:

There are nine steps in qin making, which involves woodwork, lacquering, calligraphy and music making. It takes at least a year to make one instrument.

Intricate craft:

There are nine steps in qin making, which involves woodwork, lacquering, calligraphy and music making. It takes at least a year to make one instrument.

Qin master extols craft’s heritage

January 05, 2014

A young Choi Chang-sau was enthralled to hear the extraordinary notes of the qin, also known as a guqin, or ancient stringed instrument. The son of a musical instrument shop owner, he dedicated his life to crafting them and passing on the age-old knowledge. Now 80, he is one of the world’s most celebrated qin makers, with a raft of dedicated students.

It is easy to understand Mr Choi’s fascination with the qin. It is one of the oldest plucked musical instruments in China, with a history of more than 3,000 years. A forerunner of the slide guitar, the seven-stringed instrument is known as the father of Chinese music, and the instrument of sages. Mastering the qin is traditionally regarded as the first-ranked art of the “Four Arts of the Scholar” - ahead of chess, calligraphy and painting. Qin players build their own instruments, combining the arts of crafting and performing.

The quiet, low-pitched instrument produces moving sounds that are quite different from other instruments.

“When I hear the sound of the qin, I feel very relaxed. I have made many musical instruments, including the guzheng and pipa, but I love only the sound of the qin,” Mr Choi said.

Family business

His grandfather started the business of making and selling musical instruments in the late Qing Dynasty. His father later moved the business to Hong Kong, selling guzheng, erhu and Western musical instruments - but not the qin. Determined to learn the art of qin making, Mr Choi became a student of qin master Xu Wen-jing.

The art is handed down through one-on-one instruction that aims to enlighten students. It involves several skills including woodwork, lacquering, calligraphy and, of course, music making. There are nine steps: “seeking”, “chopping”, “hollowing”, “fitting”, “assembling”, “cement priming”, “sanding”, “lacquering, and “stringing”. To make one qin takes at least one year.

In the 1950s, Mr Xu composed Jingzhai’s Inscriptions for 12 Qins and planned to make a dozen of the instruments, one for each installment of his 12-poem anthology. Choi helped to make a few of those.

Sadly, Mr Xu completed only seven instruments before his vision failed. To bring his master’s unfulfilled wish to fruition, in the 1980s, Mr Choi created a full set of 12 qins. He then turned to a celebrated Chinese scholar, poet, calligrapher and painter to help finalise the project.

“After I finished, I invited Prof Jao Tsung-I to write the calligraphy for the qins because he and my teacher were good friends. Prof Jao was glad to oblige.”

Scholarly exchanges

Prof Jao’s contribution made the set a classic, as it combined the work of three masters.

Such interactions between masters are common. In the 1980s, Mr Choi repaired a special qin from the Song Dynasty for Prof Jao. In turn, Prof Jao gave Mr Choi a painting, of a man making a qin, titled Qin Making. Mr Choi then made a qin to commemorate their friendship. The back of the qin is carved with the painting title.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, mainland China underwent a reform of musical instrument design. The art of qin making hit rock bottom during the Cultural Revolution. Still, Mr Choi continued to study qin making in Hong Kong and to help local and overseas qin musicians to repair their instruments.

In 1992, Mr Choi battled a serious illness. While he overcame it, he no longer had the strength to make qins after he recovered. His doctor, a qin player, encouraged him to pass his skills along to others.

Expertise shared

He started a qin making study class in 1993. Two years ago, Mr Choi founded the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society, to nurture qin makers and promote the qin-making art. In the last two decades, Mr Choi has introduced qin-making skills to more than 30 students.

A decade ago, UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Organisation, recognised the art of guqin music as a Masterpiece of the Oral & Intangible Heritage of Humanity. To mark the 10th anniversary of this special honour, the Hong Kong Heritage Museum and the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society have jointly organised an exhibition, "The Legend of Silk & Wood: A Hong Kong Qin Story".

The museum has reconstructed Mr Choi’s qin-crafting studio in the gallery, so visitors can see the work of qin makers, who use both their hands and hearts in the creation process.

“I think the essence of this exhibition is the relationships and humanity among the qin lovers, also between the teachers and the students. It takes a year to make a qin, so they build their qins with love and passion, and pass the torch to the next generations,” Hong Kong Heritage Museum Curator Chow Hing-wah said.

For more details about the exhibition, click here.